Almost 200 years ago, a major rebellion swept the colony of Demerara in British Guiana. It is estimated that about 12,000 enslaved people from about 55 plantations between Liliendaal and Mahaica, East Coast of Demerara participated in the revolt.

Like other uprisings in the Caribbean, this rebellion was against the grave system of African enslavement. That system ended years later in 1838, though many argue that there has been a lasting and perhaps under-recognised impact.

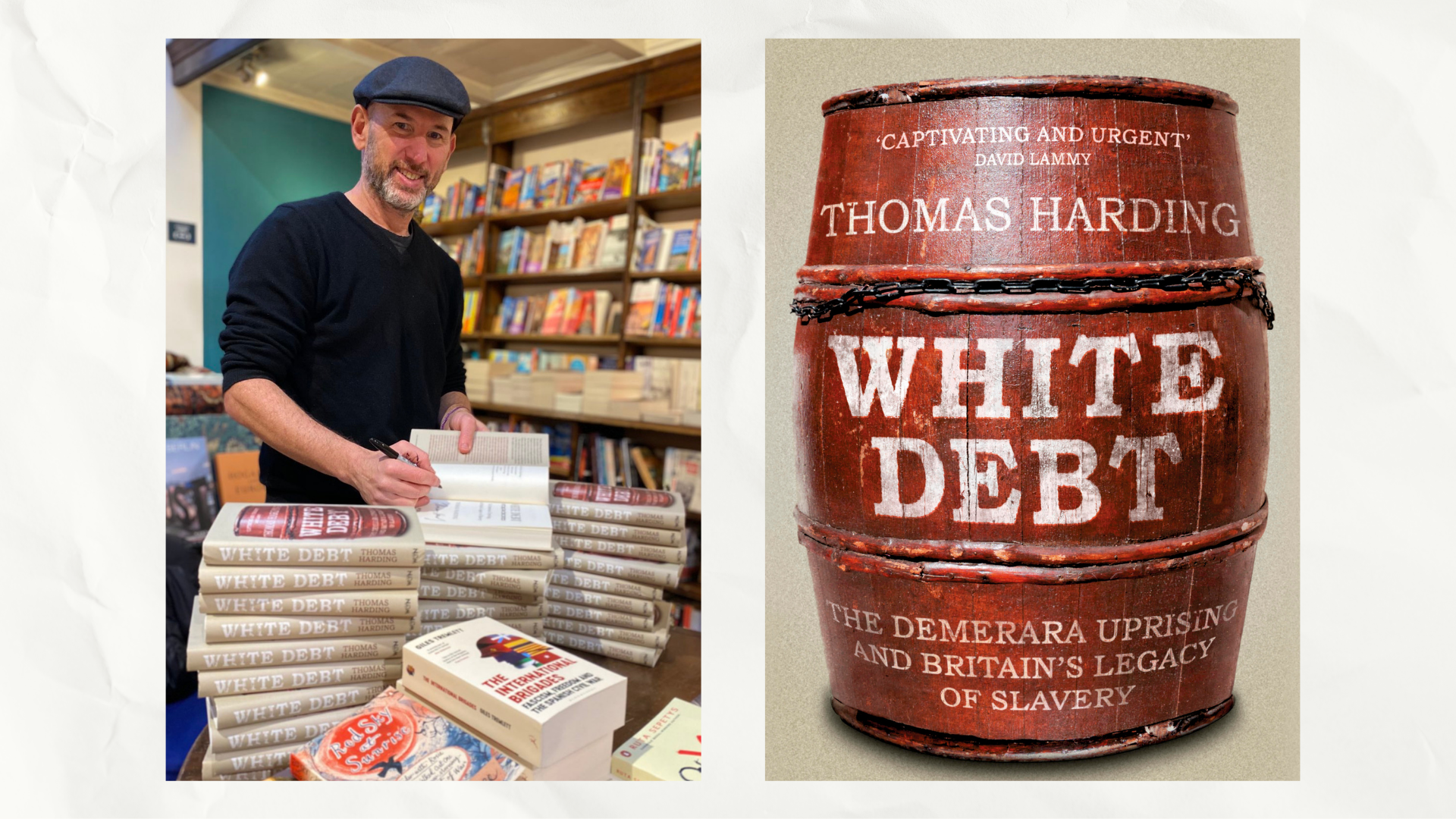

Thomas Harding, an English author, is one individual who believes in this impact and explores it in his new book ‘White Debt’.

“… for me it was a very personal journey,” Harding told the News Room during a Zoom interview on Friday.

He continued, “What Guyana presented to me, what Demerara presented to me was an opportunity to understand Britain’s role in slavery.”

The author explained that while growing up, he learnt more about enslavement in North America. His knowledge of Britain’s role in enslaving people in the Caribbean was largely rooted in portrayals of the British as the “great emancipators”.

But that’s not the full picture.

As the 1823 Demerara Uprising illustrates, Britain was integrally involved in the system of enslavement. That included the capture and transport of African people, forcing them to live and work in harsh conditions on plantations and estates, ultimately allowing White people to profit.

The more he read, Harding recognised that a profound harm had been done. And two key questions emerged: Who was responsible? What to do about it?

“The more I thought about it, it became pretty obvious who was responsible and that was White people,” he said.

And that’s how the idea of a ‘White Debt’ emerged, and that led to him immersing himself in research and also travelling to Guyana in 2020.

It’s important to note that there have been calls for an acknowledgement of this debt before now. Reparatory justice, too, has been called for.

Eric Phillips, the chairman of the Guyana Reparations Committee, had told the News Room that reparatory justice is not just about being paid a sum of money but it is also about repairing the harm done for the crime against humanity (enslavement).

In the Caribbean, calls for reparations became more formalised in 2013 when the Caribbean Reparations Commission (CRC) was established. But there has been some pushback against reparatory justice.

Harding has a close understanding of reparatory justice. He explains that his father’s family were Jewish who fled from Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Years later, his family received reparations from Germany.

Contrastingly, however, his mother’s family had a tobacco business in England in the 1800s. That means that it is likely that his family benefitted from the exploitation of enslaved people.

And because his book focuses on the role of white people in enslavement, Harding believes that the book can help move the conversation along.

“My view is, if you actually acknowledge White people’s responsibility – that’s an important first step. Then comes the questions of apology, reparations and other kinds of tangible next steps,” he said.

Harding’s efforts have not been without criticisms.

Gerard DeGroot, an author and Professor of Modern History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, was one who said that Harding’s account was flawed.

“This account of the Demerara revolt of 1823 would be better without the self- indulgent wallowing in guilt,” reads an article from DeGroot’s, published in the UK Times.

Harding acknowledges that confronting Britain’s role in enslavement is met with “a lot of defensiveness” and an inclination to point towards other seemingly more pressing issues. Even so, he is firm in his conviction.

“There is a collective responsibility, I believe,” the author emphasises.

To order Harding’s book, White Debt, people can contact Sally at One Tree Books in the UK at this address: sally@onetreebooks.com. Kindle and Audiobook versions are available from Amazon.co.uk.