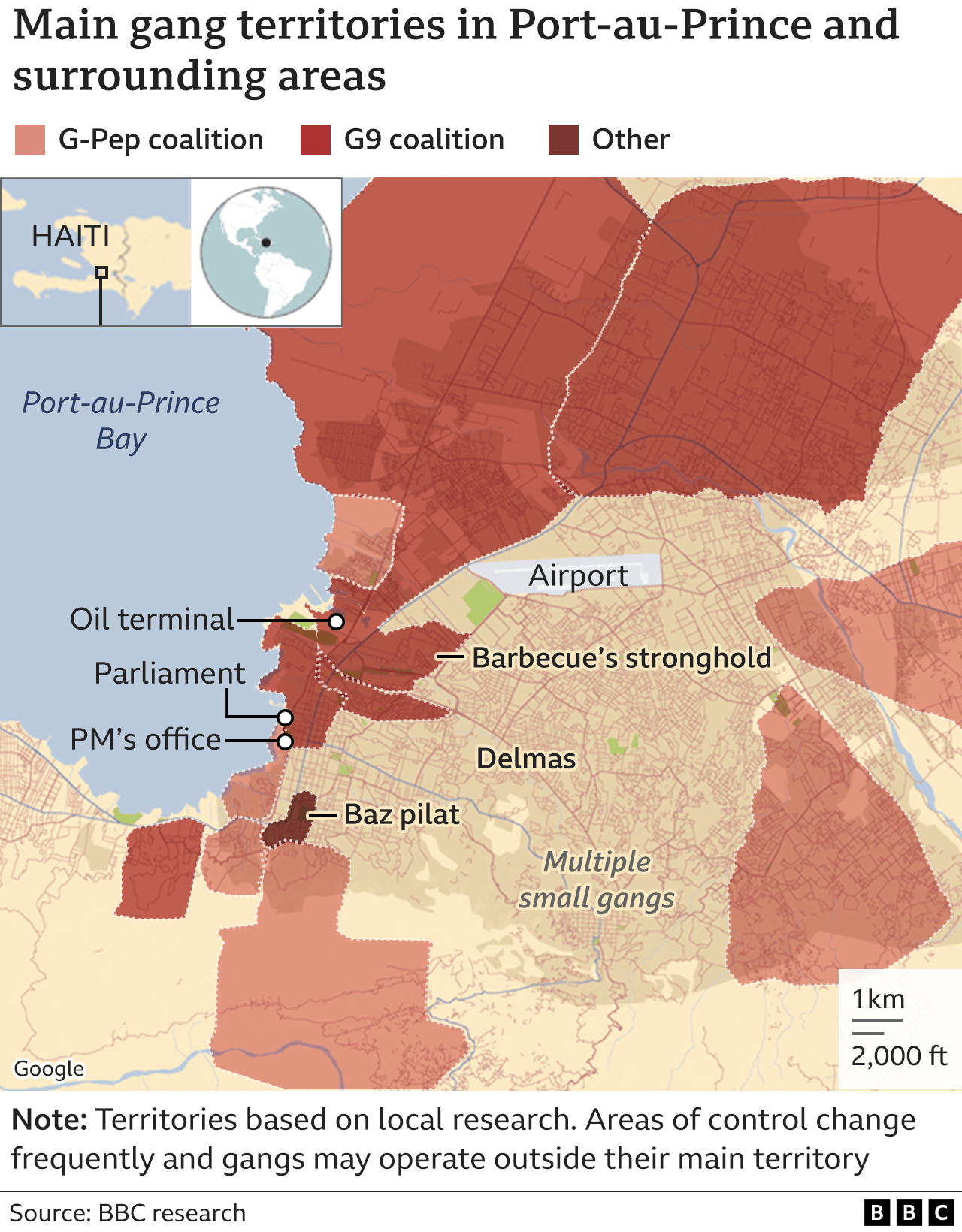

(BBC News) – In Port-au-Prince you cannot see the boundaries, but you must know where they are. Your life may depend on it. Competing gangs are carving up the Haitian capital, kidnapping, raping, and killing at will. They demarcate their territory in blood. Cross from one gang’s turf to another, and you may not make it back.

Those who live here carry a mental map, dividing this teeming city into green, yellow, and red zones. Green means gang free, yellow can be safe today and deadly tomorrow, and red is a no-go area. The green area is shrinking as heavily armed gangs tighten their grip.

Armed groups control – and terrorise – at least 60% of the capital and its surroundings, according to Haitian human rights groups. They encircle the city, controlling roads in and out. And the UN says the gangs killed almost 1,000 people here between January and June of this year.

This report contains content which some readers may find upsetting, including sexual violence

Port-au-Prince is nestled between green hillsides and the blue waters of the Caribbean. It is blanketed by heat and neglect. The rubbish is knee-deep in places – a putrid monument to a crumbling state. There is no head of state (the last one was killed in office), no functioning parliament (gangs control the area around it) and the US-backed prime minister, Ariel Henry, is unelected and deeply unpopular.

In effect the state is missing in action, as the people suffer overlapping crises. Almost half the population – 4.7 million Haitians – are facing acute hunger. In the capital around 20,000 people are facing famine-like conditions, according to the UN. This is a first for the Americas. Cholera has made a deadly comeback. But armed gangs are the greatest plague.

They set the clock here. Morning rush hour – between 06:00 and 09:00 – is peak kidnapping time. Many are snatched from the streets on their way to work. Others are targeted in the evening rush hour – from 15:00 to 18:00.

About 50 of the staff at our downtown hotel live in because it’s too dangerous for them to go home. Few here go out after dark. The manager says he never leaves the building.

Kidnapping is a growth industry. There were 1,107 reported cases between January and October of this year, according to the UN. For some gangs it’s a major income stream. Ransoms can run from $200 (£164) to $1m (£819,740). Most victims come back alive – if the ransom is paid – but they are made to suffer.

“Men are beaten and burned with materials like melted plastic,” says Gedeon Jean, of Haiti’s Centre for Analysis and Research in Human Rights. “Women and girls are subject to gang rape. This situation spurs relatives to find money to pay the ransom. Sometimes kidnappers call the relatives so they can hear the rape being carried out on the phone.”

Morning in Delmas

We travel around by armoured car. Normally that’s reserved for frontlines in warzones like Ukraine, but it’s necessary in Port-au-Prince to ward off kidnappers. It is a protection that many here can’t afford. It’s the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, prone to both natural and political disasters.

Kidnappers belong to competing gangs – which are mainly grouped into two large coalitions – G9 and G-Pep.

Driving to an early morning appointment in late November, we come across a crime scene in the middle-class suburb of Delmas 83. Bullet casings litter the pavement, glinting in the sunlight, and a man lies dead in a back alley, face down in a pool of blood.

A grey 4×4 pickup truck has veered into a wall, one side riddled with holes. An AK-47 lies on the ground beside it. Heavily armed police surround the pickup, some with faces covered and weapons drawn. Onlookers cluster together on the path. If they have questions, they don’t ask them. When you live in the shadow of the gangs, it pays to be silent.

The police tell us they were involved in a shoot-out with a group of kidnappers, out early hoping to snatch their next victim. The gang fled on foot, one of them trailing blood. The suspected kidnapper was tracked to the alley, where he was killed.

“There was a battle between an officer and the bad guys. One of them died,” says a police veteran of 27 years, who didn’t want to be named.

He says the situation in the capital has never been worse. I asked if the gangs were unstoppable. “We stopped them. Today,” he replies.

Across town that same morning Francois Sinclair, a 42-year-old businessman, heard a burst of gunfire as he was struck in traffic. He saw armed men holding up the two cars in front of him, so asked his driver to turn around. But as they tried to get away, they were spotted.

“Out of nowhere I was shot inside my own car, and there was blood everywhere,” he tells us, sitting up on a trolley in a trauma hospital run by Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF).

“I could have been shot in the head,” he says, “and there were other people in the car too.” There’s a bandage on his arm, where a bullet went straight through.

I ask if he has ever thought about leaving the country to escape the violence. “Ten thousand times,” he replies. “I couldn’t even call my mother to tell her what happened [to me] because she is getting old. The way things are here, it’s better to leave if you can.”

That’s a refrain we hear again and again, but for most Haitians, there’s nowhere to go.

The wards of the MSF hospital are full of gunshot victims, many hit by stray bullets. Claudette, who has a freshly bandaged stump in place of her left leg, tells me that she can never marry now that she is disabled. Lying nearby is 15-year-old Lelianne, who is doing a crossword puzzle to pass the time. She was shot in the stomach.

“My mom and I went out to get something to eat,” she says. “While we were ordering I felt something. That’s when I fell and screamed in agony. I didn’t expect to survive. I usually hear gunshots further away from my house. On that day they drove closer.”

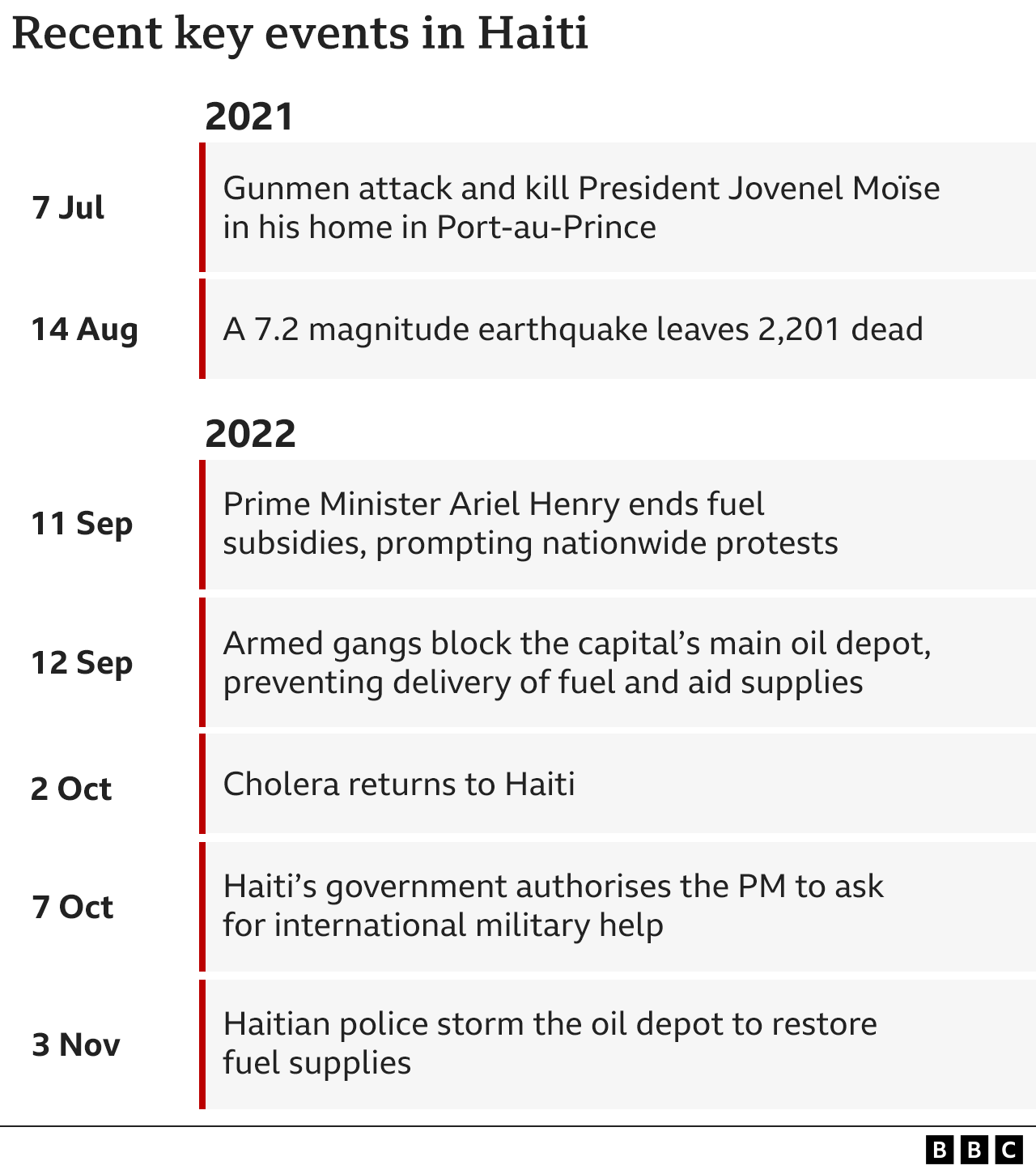

Even Haiti’s last serving president wasn’t safe in his own home. Jovenel Moise was killed by gunmen in July of 2021. Police blamed Colombian mercenaries, about 20 of whom were arrested. But more than a year later, no-one has been tried here for pulling the trigger or ordering the assassination. Human rights campaigners say four judges have come and gone from the case. It’s now in the hands of a fifth.

The killing of the president created a power vacuum which gangs have been competing to fill – with help from their friends.

Experts say that armed groups have ties to corrupt political figures – in power and in the opposition. They supply the gangs with weapons, or finance, or political protection. In return the gangs do their dirty work, generating fear, support, or instability, as required.

Wealthy businesspeople also have links to the gangs.

“There have always been relationships between politicians and some gangs, located mainly in poor neighbourhoods with high electorates. But since the election in 2011 those relationships have become institutionalised,” says James Boyard, a security expert, and professor of international relations at the State University of Haiti. “They [the gangs] are used as subcontractors to create political violence.”

Rights campaigners say there are about 200 armed groups across the country, more than half of them in the capital.

If a gang member is arrested, a phone call from their backers can get them released without delay – and with their guns. Human rights activists say there’s plenty of crime, but no punishment.

“There are no prosecutions,” says Marie Rosy Auguste Ducena, of Haiti’s National Human Rights Defence Network (RNDDH). “Judges don’t want to work on these cases. They are paid off by the gangs. And some police are like a support system for the gangs, giving them armoured cars and tear gas.”

Other officers are gang members, says rights activist Gedeon Jean. “We know that there are at least two serving or former policemen, in every gang. We know cars with police licence plates are used for kidnappings. Whether the police as an institution is involved, we don’t know.”

Some current and former police officers actually have their own gang, called Baz Pilate. Rights campaigners say it controls part of the main street in downtown Port-au-Prince.

Police collusion isn’t a mystery. Officers can earn as little as $300 a month, and some live in gang-held neighbourhoods. For them it may be a matter of survival, not choice.

A husband’s story

What’s happening here – about two hours flying time from Miami – goes well beyond mere violence. It’s as if the gangs of Port-au-Prince are engaged in a brutality contest, and anyone in this city of around one million souls can become a victim.

A slender man in his 30s – who has no gang affiliations – comes to tell us what he and his wife endured a few months ago. His neighbourhood is controlled by a gang, whose rivals came on a killing spree. For his safety we are not naming the area, or the armed group involved.

When he initially starts to speak, he carries on for 13 minutes without stopping – as if he cannot hold in his words or his anguish.

“I told myself the shots are too close to us, and we should try to leave,” he says. “But they were already storming the neighbourhood. I went back inside the house with my wife. I was so scared I was shaking. I did not know what to do. They mostly kill young men. My wife hid me under the bed and covered me with a pile of clothes. My nephew was hiding in the wardrobe.”

Soon men entered the house, hitting his wife, and demanding information on local gang members. When his nephew tried to run, they shot and killed him. The husband remained in hiding, and in torment.

“I wanted to run away. I wanted to cry out. What hurts me the most is that when I was under the bed, I couldn’t see but I could hear those men raping my wife. They were raping her, and I was under the bed, and I could say nothing.”

Afterwards their house was burned, and he and his wife fled in different directions. They are still living apart, staying with friends and relatives, but he hopes they can set up home again with their young child.

What happened “is a scar that affects the body and the soul”. His wife is now pregnant, and they do not know if he is the father, or if it is one of the attackers. Either way, he says he will accept the child and give it his name.

“What I endured was nothing,” he says. “There is a lady who had only one child. They cut his throat in front of her. The young man who was not in a gang.”

Husband and wife have been robbed of almost everything, including their love for their country. “Haiti is erased from our hearts,” he says. “Any chance we get, we will leave.”

At that he breaks down, his chest heaving as he weeps.

The testimonies I have gathered here are among the worst I have ever heard in more than 30 years as a foreign correspondent, reporting from over 80 countries. And it feels like we have barely scratched the surface.

For the gangs of Port-au-Prince, there are no limits.

In just a few days, I met three victims of gang rape – the youngest only 16. She and a relative were raped by the same attackers, who threated afterwards to burn them alive inside their house. The other woman was six months pregnant at the time she was attacked. As she was being set upon, her husband was led away to his death. Months on she has not been able to find his body.

Increasingly, rape is used as a weapon by the gangs. They target women and girls living in areas controlled by their rivals. During a turf war in July in Haiti’s poorest district, the sprawling Cité Soleil. Campaigners say more than 300 people were murdered – most of the bodies were charred – and at least 50 women and girls were gang raped.

Haiti’s National Human Rights Defence Network (RNDDH), which has documented the rapes in Cite Soleil, says many survivors “regret being alive”. Twenty of them were raped in front of their children. Six saw their spouses being killed before being gang raped.

Most of Cité Soleil is controlled by the most powerful gang federation in Port-au-Prince – the G9 family and allies. Local sources say it had close ties to the assassinated president and his ruling party, and its speciality is extortion.

G9 blockaded the main fuel terminal in the city in September, paralysing the country for almost two months, and triggering a humanitarian crisis.

Its leader is a former police officer called Jimmy Cherizier, nicknamed “Barbecue”, who occasionally holds press conferences. We requested an interview through intermediaries, but had no response. He may be less talkative these days because he’s recently been put under sanctions by the UN Security Council, accused of threatening the peace and stability of Haiti.

The United States and Canada recently sanctioned two Haitian politicians, including the sitting president of the Senate, Joseph Lambert, for allegedly collaborating with the gangs.

Sources here say the sanctions are having some impact because politicians who use the gangs now want to lie low.

‘Criminals have taken a country hostage’

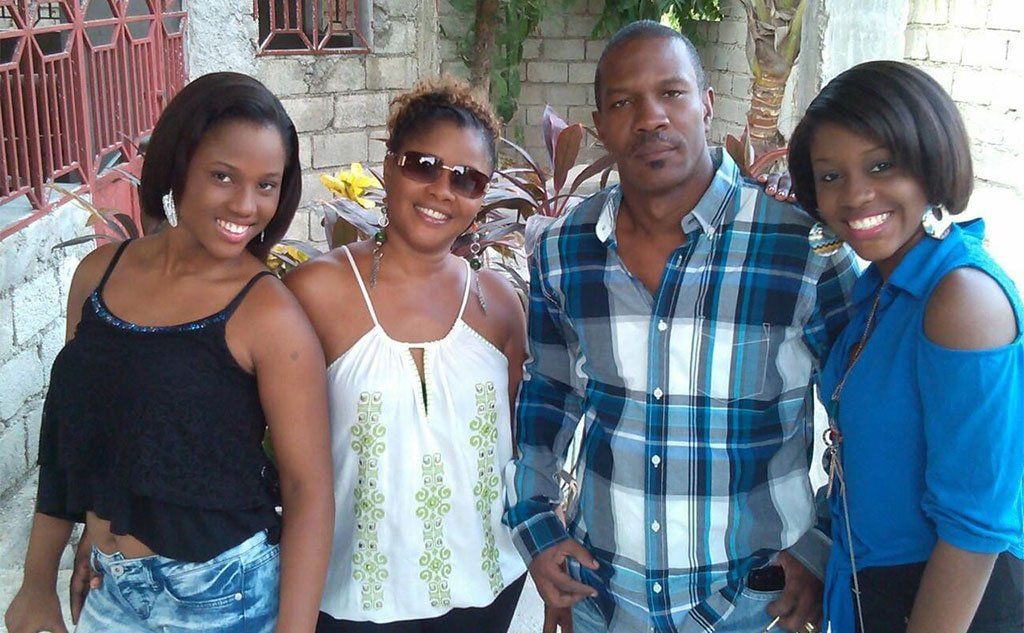

When Jean Simson Desanclos reached the deserted street at the edge of a gang-ridden suburb, he found nothing of his family except the burnt-out shell of the family’s Black Suzuki. The charred remains of his wife and two daughters had already been taken to the morgue.

Josette Fils Desanclos, 56, was taking one daughter Sarhadjie, 24, to university, and the other, Sherwood Sondje, shopping for her birthday. She was about to turn 29. Both girls had studied law like their father. They were his “princesses”.

“On 20 August I lost everything,” he says. “And it wasn’t just my family. In all, eight people were killed that day. It was a massacre.”

Mr Desanclos believes his wife and daughters resisted a kidnap attempt and were shot by a notorious gang called the 400 Mawazo, who were expanding their territory. “I point my fingers at them,” he says. The killings happened on the outskirts of an area called Croix des Bouquet, which was already under the gang’s control.

Mr Desanclos, who is softly spoken and smartly dressed, is a lawyer and human rights activist. He is now a man bereft – longing for the voices he will never hear again.

“You are always waiting for a call from your child telling you, ‘Dad this’ or ‘Dad that’. I lost the love of my life and the two children we raised in this difficult country. It’s like you are a multi-millionaire and suddenly, you are poor.”

Despite the risk to himself, he is seeking justice for his wife and daughters. “Family is a sacred thing. Not pursuing justice would be betraying them,” he says. “My daughters know their father is a fighter, who never abandons people, much less his own family. The risk is enormous, but what more can I lose now?”

He wants the world to understand one thing about the Haiti of today – that the gangs have free rein.

“Criminals have taken a country hostage,” he says. “They make their own laws. They kill. They rape. They destroy. I would like my daughters to be the last sacrifice, the last young women killed.”

He speaks with dignity, and conviction, but knows his wish may not be granted.

In Haiti, it is the gangs that function, rather than the state. Prime Minister Ariel Henry cannot even reach his own office because armed groups control the area. We made several requests for an interview with him, but these were declined.

Haiti’s government – such as it is – has issued “a distress call” for an international force to help restore order.

There’s talk at the United Nations about the need for a non-UN armed force, but no-one seems in a hurry to lead it, or even to take part.

Foreign interventions have a bad name, and a bad history here. The last UN mission is remembered for allegations of sexual abuse, and for bringing cholera to Haiti, via UN peacekeepers from Nepal. The epidemic killed around 10,000 people.

There are mixed views here on the idea of foreign boots on the ground. There’s support from some in business – who have used armed groups but now want them reined in – and from those trapped in gang-controlled areas. There’s opposition from civil society leaders who say Haiti needs to go it alone.

While the international community debates and demurs, it is massacres as usual for the gangs.

Local sources say armed groups are brutally expanding their territory because elections are overdue. When politicians come looking for votes – in gang held areas – they have to pay off the gunmen.

The latest atrocity was at the northern entrance to Port-au-Prince on 30 November. According to local media reports, some in the area spotted armed men – from an emerging gang – trying to gain a foothold, and informed police.

The gunmen retaliated at night, killing at least 11 people. Some of the bodies were set alight.

The boundaries here are once again being redrawn in blood. Those living in the city need to update their mental map, as one more area is turning from green to red.