Money from trees: What of Indigenous people and their rights? And do they benefit from the carbon trade?

By Neil Marks

After years of campaigning by Guyana and other forest-rich nations, there is finally a mechanism to value the carbon dioxide stored in trees and to pay countries which have kept their forests standing. Guyana is the first country to benefit and is set to receive hundreds of millions of United States dollars.

But some representatives of indigenous groups in Guyana say land rights of indigenous peoples, who have lived in and protected the forests for generations, haven’t been respected in the way the government hammered out the deal. They claim their right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent was violated – that they didn’t have the chance to either accept or reject it.

“Guyana’s government has said many times in global climate talks that Guyana has high forest coverage and low deforestation.

“What they haven’t told the world is why. These forests exist because of the Indigenous peoples that live there and protect them,” Laura George of the Amerindian Peoples Association (APA) told a forum at New York University last Monday.

She says indigenous people want to have a greater say in what happens to the forest and how decisions are made.

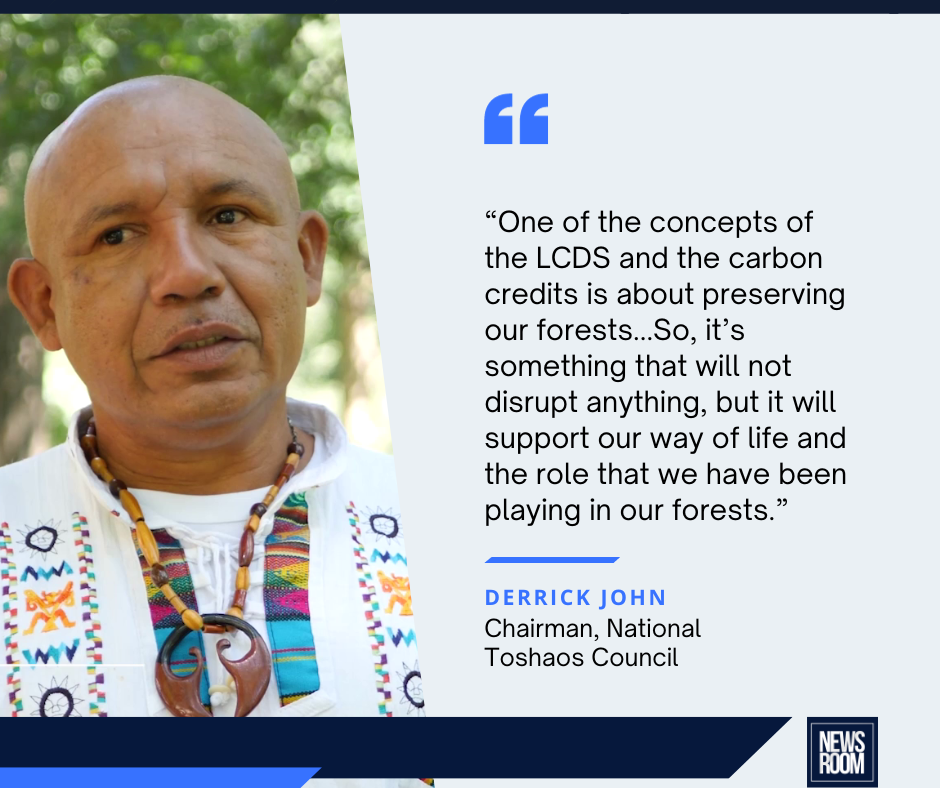

But Derrick John, the chief of chiefs of Guyana’s indigenous (or Amerindian) communities says indigenous peoples have had their say. He accuses the APA of pushing a false narrative and says there are but just a few dissenting voices.

So, what’s the story?

Guyana’s forests

Guyana’s total land area is 21 million hectares with 85% of it, or roughly 18 million hectares, covered by trees of various kinds.

Those trees store 19.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide, a gas which traps heat. The carbon dioxide, or carbon for short, along with other harmful gases are causing the earth’s temperature to rise, leading to climate change, leading to extreme weather events such as floods, wildfires and more frequent and intense hurricanes.

How is Guyana helping?

Guyana has avoided cutting down trees to clear land for big agriculture and mining projects like other countries have done to earn money for national development projects.

In return, the country has argued there must be value – it must earn – in keeping the forest standing.

| Climate economist Pradeepa Bholanath explains the value of standing trees. She also explains the platform Guyana is using to earn from the carbon stored in its forest. (Filmed by Leon Gonsalves and edited by Shatanand Anude)

Over recent decades, there have been global efforts to protect the rainforest and to provide money to countries which have been doing so. This would give them an incentive to continue with sustainable forestry practices – protecting the forest while earning from it.

That has resulted in what is called ART TREES.

What is ART TREES?

The campaign to pay countries which avoid deforestation has been mainly waged through the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where countries came up with a mechanism called REDD+.

REDD stands for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. So, basically, save the trees and avoid letting all that carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which is what would happen if the trees were cut down. The “+” refers to all other activities that help to protect the climate, such as management plans that ensure the forests are used in a sustainable way.

That brings us to ART TREES.

ART means the Architecture for REDD+ Transactions. It’s an independent programme guided by all the efforts over the years, including those at the UNFCCC, to compensate countries which have avoided deforestation.

The way ART measures, monitors, and verifies Guyana’s carbon stock is through TREES, which stands for The REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard. The standard is the set of guidelines, or the measuring tool, used to decide on the integrity or quality of Guyana’s carbon.

Once ART TREES verifies how many trees a country has and how much carbon those trees store, it certifies it, and a country is issued carbon “credits”. One credit is equal to one ton of carbon dioxide.

“The concept was to find a way to value something that wasn’t valued before – that is the storage function of trees – storing carbon dioxide,” says Pradeepa Bholanath, a climate economist.

“To establish that fact required a system of certification – and for an international standard to say, yes, you have this amount of carbon dioxide, yes, your trees shown potential to store carbon…and this contributes to the global solution for climate action.”

Late last year, after years of monitoring and evaluation, Guyana became the first country to be issued carbon credits by ART TREES. The amount? 33.4 million for the period 2016 to 2020.

Those credits are then placed on an electronic register by ART TREES so companies can see what is available. What Guyana did was to issue a public call for proposal for companies to buy those credits.

HESS, the American oil company, decided to put in a proposal and bought 1/3 of the credits issued to Guyana. How is the value of a credit determined? That’s thrashed out between the buyer and the seller.

Even though credits have not yet been issued beyond 2020, the system of verification and validation is ongoing, and it is likely Guyana will be issued credits for the years after then.

HESS decided to buy in all the way up to 2030 and is paying US$750 million after negotiations with the government.

Why is HESS paying Guyana to preserve trees?

The issue goes back to global efforts to fight climate change, starting with a pledge made by world leaders in Kyoto, Japan in 1997. Guided by those who study the climate and its changes, world leaders agreed that there should be a limit to carbon dioxide emissions and slow down the rate of global warming.

That led to the development of markets to buy and sell carbon as a way by which big polluters can offset their emissions of carbon and countries can earn money by keeping their trees intact.

Countries within the European Union are part of what is called the “compliance” market. This is a system whereby countries tell their companies how much carbon they are allowed to emit in their operations. If they go over the allowed limit, then they must buy carbon credits, which acts like a permit to allow them to emit more than they should. It is meant to pressure companies to find better ways of carrying out their operations, so they stay within the limit or pay big if they go over.

Then there is the “voluntary” market. This is the system whereby companies aren’t mandated to buy credits; they just do it because they want to. Why would they do that? Perhaps to look good in the eyes of the public. Or because is part of their Corporate Social Responsibility, where they account to themselves, their stakeholders and the public, showing that they are conscious of the impact their operations are having on the environment.

Hess voluntarily decided to pay Guyana for preserving its trees.

What is Guyana doing with the money it has earned?

The money goes towards national development projects which do little to pollute the planet. These projects fall within the government’s Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS), which is the blueprint or the plan by which the country intends to drive national development while maintaining its reputation of being a country with high forest cover with a very low deforestation rate.

It was determined that 15% of the carbon payments would go to indigenous communities. Guyana has nine indigenous nations, and they make up about 10 per cent of Guyana’s population.

So, what’s the problem?

There are groups critical of the government on indigenous rights issues. The main organisation is the APA, mentioned at the outset. They do not approve of the carbon market trade because they claim communities, they work with were not properly made aware of it.

The APA’s Laura George and other critics were hosted by New York University’s Law Department last Monday.

“…this is indigenous peoples’ lands,” George said, and consent wasn’t given to say, “we are interested in the carbon trade and we agree to 15%.”

Immaculata Casimero, a native of the Wapichan people, went further, saying her people are “afraid of being restricted” in the use of their lands because of the carbon trading deal.

“We depend on the land for livelihoods,” she said.

“…when we do not have money in our pockets, we go there to fish, we go there to hunt, we go there to gather.

“… we fear, that they might have restrictions, you know, rules and guidelines will be made to say how we use our forests.”

| Audio recording of Laura George and Immaculata Casimero at the forum “Carbon Markets and Rights: Indigenous Peoples’ Perspectives on the Approval of ART TREES Credits in Guyana”. The forum was put on by NYU Law’s Global Justice Clinic.

The village chiefs disagree

Village leaders see no problem.

Village leaders are called toshaos and they all meet for a national conference every year.

The National Toshaos Council, made up of all of the country’s toshaos (or village chiefs), has expressed support for the carbon trade and sees no harm to indigenous peoples or territories. Their support for the LCDS and the carbon trade is detailed in a resolution they adopted in July 2022.

Derrick John is the chairman of the Council. He says the Council is guided by what most of the people in the villages want.

He dismisses concerns that the work done in communities did not meet the benchmarks for consultation and Free, Prior and Informed Consent by indigenous communities.

“There was a lot of brainstorming” and “general meetings in villages” and villagers selected a steering committee to put the idea together in a format and presented these to the government to be funded.

The projects are diverse, but most deal with sustainable forestry operations, food security and income-generating activities such as eco-tourism.

“One of the concepts of the LCDS and the carbon credits is about preserving our forests,” John says.

“So, it’s something that will not disrupt anything, but it will support our way of life and the role that we have been playing in our forests.”

As of September, G$2.9 billion in payments have gone to 225 indigenous communities; 17 communities are left to receive payments.

| Table shows payment distribution to indigenous villages in the regions they live. As of September, 225 communities received payments and the remaining 17 are due to receive theirs.

In Aishalton, where Casimero lives, villagers have decided on support to farmers, construction of a village kitchen, support to women for broiler production, purchase of a tractor-trailer and renovation and extension of the Primary School kitchen.

John says Casimero and the APA do not speak for the 242 villages which have backed the carbon trade. No community has rejected the deal.

“While I disagree with their efforts and their goals, I support their right to put forward their position wherever and whenever they want.

“However, I do not support their attempts to claim that they speak for indigenous peoples – and it is important that their attempts to do so are rejected,” John said in a letter to NYU.

“…Guyana’s 242 villages and communities produced village plans and chose to participate in the carbon credits programme (in all instances, the proposal got well over two-thirds support from those present).

“They are investing this money in the priorities chosen by communities themselves and expressed in their village plans,” John added in his letter.

| Chairman of the National Toshao’s Council Derrick John disagrees that indigenous peoples’ rights were violated in Guyana’s carbon deal with Hess Corporation.

Bholanauth, mentioned above, was among those leading Guyana’s efforts to secure carbon credits. She says the support to indigenous communities is all-encompassing and there is no distinction in how a community is defined.

So there is no stipulation for the village to be titled to receive payments and regard was paid to customary lands. And there was no distinction made if communities from a particular region should or should not get funding. So whether they live in and around forests, wetlands or savannahs does not matter in the benefit sharing agreement.

Further, Bholanauth says the scheme does not in any way envisage any changes to the way in which indigenous peoples have used the land and forest and there is no plan to introduce any restrictions.

“There is no recommended change in terms of how villages operate,” she emphasises.

“The one thing that is different is that all those ideas and projects that villages would have had banking up for many years, there is now a way to get that done,” she says. That way is to provide resources, thanks to money earned from the carbon sale.

The chief of chiefs, Derrick John, agrees.

“It gives us that additional support where we can continue to do the work our ancestors did in years gone by.”